Only nine percent of plastic waste is recycled worldwide, while the rest is either incinerated or dumped into landfills.

Researchers at the University of Copenhagen have developed a biodegradable plastic from barley starch blended with fiber from sugarbeet waste.

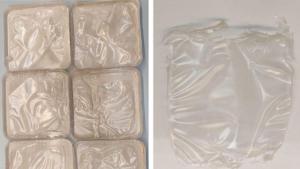

The new material, which decomposes in nature in just two months, can be used for food packaging and other things.

The new material also reduces the climate footprint of plastic production. “We have an enormous problem with our plastic waste that recycling seems incapable of solving,” said Professor Andreas Blennow of the Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of Copenhagen.

________________________________________________________________________

Read Also : Recycling For Profit: How This Hyderabad Woman Is Creating New Frontiers In Urban Waste…

________________________________________________________________________

New type of bioplastic that is stronger

The scientists have created a new bioplastic that is more robust and resistant to water than existing types.

“We’ve developed a new type of bioplastic that is stronger and can better withstand water than current bioplastics. At the same time, our material is one hundred percent biodegradable and can be converted into compost by microorganisms if it ends up somewhere other than a bin,” Blennow said.

Researchers have maintained that only nine percent of plastic waste is recycled worldwide, while the rest is either incinerated or dumped into landfills.

Blennow also claimed that bioplastics already exist, but they aren’t 100% degradable. Only a limited part of them is degradable under special conditions in industrial composting plants.

He stressed that using bioplastic terms for such material is actually misleading.

“I don’t find the name suitable because the most common types of bioplastics don’t break down that easily if tossed into nature,” he added.

________________________________________________________________________

Read Also : Situation of Waste Management Start-ups in India

________________________________________________________________________

“The process can take many years and some of it continues to pollute as microplastic. Specialized facilities are needed to break down bioplastics. And even then, a very limited part of them can be recycled, with the rest ending up as waste.”

Main ingredients are amylose and cellulose

The new material is so-called biocomposite and its main ingredients are, amylose and cellulose, which are common across the plant kingdom.

Researchers developed a new type of barley variety that produces pure amylose in its kernels. Notably, pure amylose is far less likely to turn into a paste when it interacts with water compared to regular starch.

Cellulose is a carbohydrate found in all plants and we know it from cotton and linen fibers, as well as from wood and paper products. The cellulose used by the researchers is a so-called nanocellulose made from local sugar industry waste. And these nanocellulose fibers, which are one thousand times smaller than the fibers of linen and cotton, are what contribute to the material’s mechanical strength, reported Phys.org.

________________________________________________________________________

Read Also: Sustainable Farming and its Relationship with Soil Biodiversity

________________________________________________________________________

Durable, flexible material could be used for shopping bags

Blennow also highlighted that amylose and cellulose form long, strong molecular chains.

“Combining them has allowed us to create a durable, flexible material that has the potential to be used for shopping bags and the packaging of goods that we now wrap in plastic.”

Researchers maintained that the new biomaterial is produced by either dissolving the raw materials in water and mixing them together or by heating them under pressure. By doing so, small “pellets” or chips are created that can then be processed and compressed into a desired form.

Blennow claimed that his team is quite close to the point where we can really start producing prototypes in collaboration with our research team and companies.

“I think it’s realistic that different prototypes in soft and hard packaging, such as trays, bottles and bags, will be developed within one to five years,” added Blennow.

NOTE – This article was originally published in interestingengineering and can be viewed here