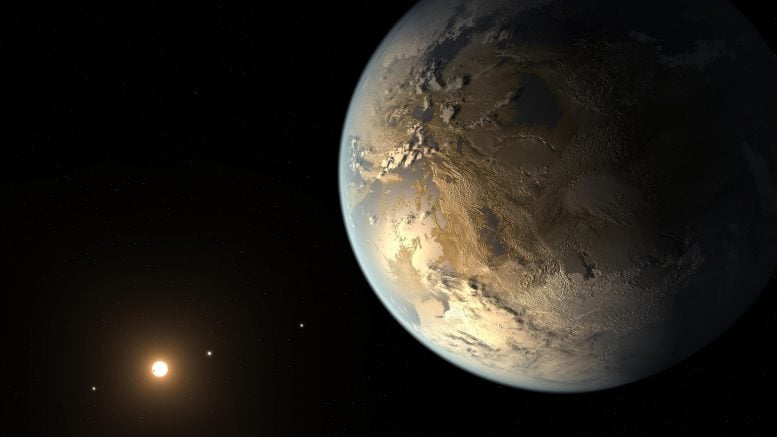

What happens if we search the cosmos for signs of life and come up empty? Researchers explored the scientific value of a “null result” and how it could still reveal how rare life might be. Credit: SciTechDaily.com

What happens if we search the cosmos for signs of life and come up empty? Researchers explored the scientific value of a “null result” and how it could still reveal how rare life might be. Credit: SciTechDaily.com

Even if no life is found on other planets, smart survey design and careful statistics can still reveal how rare, or common, life really is in the universe.

What happens if we scan dozens of distant planets for signs of life, and find nothing? A team led by Dr. Daniel Angerhausen, a physicist in the Exoplanets and Habitability Group at ETH Zurich and a VEGETARIAN KETO DIET PLAN FOR INDIANS – LOSE 15 KGS IN A MONTH

________________________________________________________________________

How Many Planets Are Enough?

The researchers found that if 40 to 80 Earth-like exoplanets were surveyed and none showed signs of life, a so-called “perfect” null result, we could reasonably conclude that less than 10 to 20 percent of similar planets host life. In our galaxy, that 10 percent would still translate to around 10 billion potentially inhabited planets. Even without detecting life, this kind of result would allow scientists to place a meaningful upper limit on how common life might be across the cosmos, something that has remained elusive until now.

But there’s a catch. Even a “perfect” null result comes with uncertainty, which can affect how reliable the conclusions are. One kind of uncertainty, known as interpretation uncertainty, involves the risk of false negatives – cases where signs of life are present but go undetected. Another, called sample uncertainty, involves biases in the types of planets selected for observation. For instance, if the sample includes planets that aren’t truly capable of supporting life, the results could be misleading. Understanding and accounting for these uncertainties is essential to making sound scientific inferences from future planet-hunting missions.

Asking the Right Questions

“It’s not just about how many planets we observe – it’s about asking the right questions and how confident we can be in seeing or not seeing what we’re searching for,” says Angerhausen. “If we’re not careful and are overconfident in our abilities to identify life, even a large survey could lead to misleading results.”

_______________________________________________________________________

Read Also : What to know about the vegetarian diet

________________________________________________________________________

Such considerations are highly relevant to upcoming missions such as the international Large Interferometer for Exoplanets (LIFE) mission led by ETH Zurich. The goal of LIFE is to probe dozens of exoplanets similar in mass, radius, and temperature to Earth by studying their atmospheres for signs of water, oxygen, and even more complex biosignatures. According to Angerhausen and collaborators, the good news is that the planned number of observations will be large enough to draw significant conclusions about the prevalence of life in Earth’s galactic neighborhood.

Still, the study stresses that even advanced instruments require careful accounting and quantification of uncertainties and biases to ensure that outcomes are statistically meaningful. To address sample uncertainty, for instance, the authors point out that specific and measurable questions such as, “Which fraction of rocky planets in a solar system’s habitable zone show clear signs of water vapor, oxygen, and methane?” are preferable to the far more ambiguous, “How many planets have life?”

Bayesian vs. Frequentist Perspectives

Angerhausen and colleagues also studied how assumed previous knowledge – called a prior in Bayesian statistics – about given observation variables will affect the results of future surveys. For this purpose, they compared the outcomes of the Bayesian framework with those given by a different method, known as the Frequentist approach, which does not feature priors. For the kind of sample size targeted by missions like LIFE, the influence of chosen priors on the results of the Bayesian analysis is found to be limited and, in this scenario, the two frameworks yield comparable results.

_______________________________________________________________________

Read Also : 6 Excellent Sources Of Vegetarian Protein For Your Daily Diet

________________________________________________________________________

“In applied science, Bayesian and Frequentist statistics are sometimes interpreted as two competing schools of thought. As a statistician, I like to treat them as alternative and complementary ways to understand the world and interpret probabilities,” says co-author Emily Garvin, who’s currently a PhD student in Quanz’ group. Garvin focussed on the Frequentist analysis that helped to corroborate the team’s results and to verify their approach and assumptions. “Slight variations in a survey’s scientific goals may require different statistical methods to provide a reliable and precise answer,” notes Garvin. “We wanted to show how distinct approaches provide a complementary understanding of the same dataset, and in this way present a roadmap for adopting different frameworks.”

The Power of Just One Discovery

This work shows why it’s so important to formulate the right research questions, to choose the appropriate methodology and to implement careful sampling designs for a reliable statistical interpretation of a study’s outcome. “A single positive detection would change everything,” says Angerhausen, “but even if we don’t find life, we’ll be able to quantify how rare – or common – planets with detectable biosignatures really might be.”

NOTE – This article was originally published in scitechdaily and can be viewed here

Tags: #Astrobiology, #climate, #earth, #environment, #Exoplanet, #getgreengetgrowing, #gngagritech, #greenstories, #nature, #oxygen, #planet, #skies, #water