Abstract

One challenge in climate change communication is that the causes and impacts of global warming are unrelated at local spatial scales. Using high-resolution datasets of historical anthropogenic greenhouse emissions and an ensemble of 21st century surface temperature projections, we developed a spatially explicit index of local climate disparity. This index identifies positive (low emissions, large temperature shifts) and negative disparity regions (high emissions, small temperature shifts), with global coverage. Across all climate change projections we analyzed, 99% of the earth’s surface area has a positive index value. This result underscores that while emissions are geographically concentrated, warming is globally widespread. From our index, the regions of the greatest positive disparity appear concentrated in the polar arctic, Central Asia, and Africa with negative disparity regions in western Europe, Southeast Asia, and eastern North America. Straightforward illustrations of this complex relationship may inform on equity, enhance public understanding, and increase collective global action.

_______________________________________________________________________

Buy Organic Products Online at best prices at https://www.getgreen.co.in .

_______________________________________________________________________

INTRODUCTION

Climate change presents a series of unprecedented challenges to natural and human systems (1, 2). Despite the ongoing public debate on the causal role of anthropogenic greenhouse (GH) emissions (3–5), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) determined through a near-unanimous scientific consensus that forcing from anthropogenic emissions is the primary driver of climate change (6). Reducing GH emissions, mitigating current and predicted consequences, and building resiliency have therefore become principal topics at the interface of science and public policy, across political scales (2). In addition, public dialogues are increasingly expressing the need to develop a concerted and urgent global response to address climate change that also explicitly recognizes and addresses problems of inequity (7). To date, however, broad international implementation of climate change action has been elusive (8).

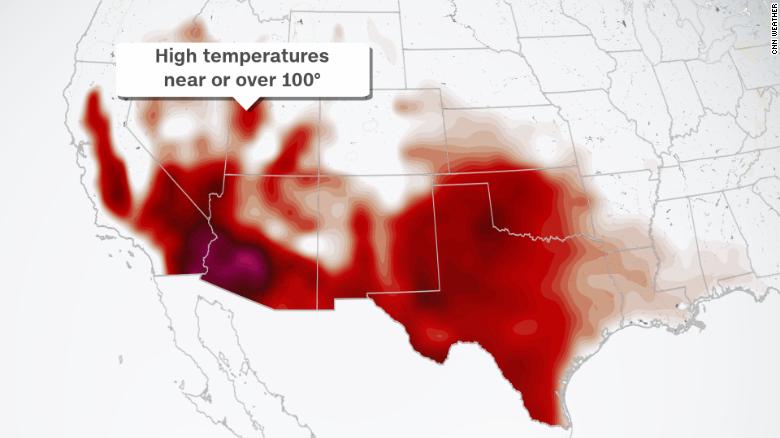

Why has it been so challenging to develop a global response to anthropogenic climate change? The answer, in part, relates to climate change manifesting a classic problem of collective action (2, 9). One obstacle to collective action may be rooted in the public understanding of the complex (10) and nonlinear nature of the emissions and climate change relationship. Anthropogenic GH emissions, for example, are concentrated in densely populated regions (see Fig. 1A), mostly in the northern hemisphere from 30° to 55°N (Fig. 1B and figs. S1 and S2). These emissions, however, disperse throughout the planet’s atmosphere and manifest their warming effects worldwide, although warming is especially amplified above 60°N in the polar arctic (Fig. 1, C and D, and fig. S3) (11). A result of this pattern of geographic asymmetry is that less than 8% of the earth’s surface area has generated 90% of historical GH emissions (Fig. 1A and fig. S4). While emissions are concentrated, however, more than 51% of the earth’s surface is projected to warm by at least 3°C before the end of the 21st century (Fig. 1C and fig. S4) under the Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 8.5 scenario. [The RCP scenario 8.5 tracks cumulative CO2 emissions accurately in history and the near future (12, 13).]

(A) Anthropogenic GH emissions (CO2, BC, CH4, and N2O) averaged from 1970 to 2018, (B) summarized in columnar form by 1° latitude means. (C) Multimodel ensemble of surface air temperature departures for the RCP 8.5 scenario over 2050–2099 relative to the 1956–2005 temperature baseline, (D) also averaged in 1° latitude bins. Extreme emissions are largely concentrated in human population centers (see fig. S18), while extreme temperature shifts are widespread at high latitudes. By comparison to land, the ocean has a lower amplitude in both datasets, with few emissions and lower projected temperature shifts.

When combined, geographical asymmetries between emissions and their projected warming reveal steep inequalities. Regions within western Europe and East Asia, for example, emitted 1.6 kg m−2 year−1 of combined GH emissions over 1970–2018 for every 1°C of projected warming from 2050 to 2099 (RCP 8.5; results mapped in fig. S5). At the same time, much of the polar arctic has zero GH emissions yet is projected to warm by more than 8°C (Fig. 1). Therefore, the impacts of climate change are not constrained to regions of high anthropogenic GH emissions, and the emission-warming relationship is essentially decoupled and statistically independent at the local scale. This spatial nonstationarity likely masks the far-reaching and transboundary consequences of local GH emissions from the public and contributes to the lasting consensus gap on climate change (14, 15).

_______________________________________________________________________

Read Also : Greenhouse emissions shrinking stratosphere: Ozone layer at risk as study predicts further decline

________________________________________________________________________

To illustrate and inform on these issues, here, we derive a local index of climate disparity using empirical datasets of anthropogenic emissions and simulations of future climate change impacts. The recent availability of reanalysis products from archived observations of the primary GH emission agents—carbon dioxide (CO2), black carbon (BC), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) (16, 17)—provides a fresh opportunity to examine the geography of the emission–climate change relationship. We aggregate these emission data and compare them to future climate simulations from the fifth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5) to generate an index of local climate disparity with global coverage. Through our analysis, we aim to help clarify the inherent complexity of anthropogenic climate change across ecological and geopolitical boundaries. This study is a contribution to the ongoing climate change dialogue addressing the global equity and collective action problem. We hope that this informs public understanding, which, in turn, may urge collective action on effective climate mitigation and adaptation measures.

RESULTS

Relating local GH emissions to local projected temperature shifts

Collectively, CO2, BC, CH4, and N2O account for 91.8% of the current global radiative forcing (total = 3.86 W m−2; see table S1 for details), which is considered the human contribution to global warming (18). Figure 1A plots the annual average of anthropogenic GH emissions, globally, from 1970 to 2018 at a 1° × 1° resolution. This shows known hot spots in industrialized population centers, peaking in the northern hemisphere (Fig. 1B). The CMIP5 model simulations provide the ensemble mean of projected changes in atmospheric, ocean, and biogeochemical variables (19). From these outputs, Fig. 1C extracts the ensemble mean anomaly surface temperatures, illustrating the marked warming in the Arctic Circle (Fig. 1D). The CMIP5 ensemble means represent a robust projection of future climate (6) that can distinguish signal from noise (see discussion in fig. S25).

From our aggregated high-resolution emission dataset and projected temperature shifts, we derive a local climate disparity index (LCDI) that captures the localized disparity between emissions and projected warming. This LCDI illustrates the magnitude of the spatial disconnect between the cumulative emissions (Fig. 1A) and surface temperature anomalies (Fig. 1C) during the 21st century. We generated global LCDI summaries for four CMIP5 projections, using the RCP 4.5 and 8.5 scenarios each over two 21st century periods 2005–2055 and 2050–2099 (6). The pairing in Fig. 2A of the aggregated anthropogenic GH emissions and ensemble temperature anomalies demonstrates that there is no apparent relationship between the two variables at the local scale. This further revealed a highly skewed positive/negative LCDI area ratio (99:1), globally, across all future climate simulations (fig. S6). This skew suggests an extreme geographic imbalance between areas expected to experience temperature shifts while contributing relatively minimal local emissions as well as the reverse. The global visualization of LCDI illuminates the contours between positive and negative LCDI regions (Fig. 2C and fig. S7), capturing both the heterogeneity and independence in the underlying data layers. Broadly, terrestrial regions above 60°N have the highest positive LCDI owing to the combination of pronounced warming (2, 6) and negligible GH emissions. Densely populated centers of economic production in Europe, Asia, and North America have the lowest negative LCDI due to heavy emissions with comparatively mild warming (Fig. 1C).

(A) Pairwise scatter plot of combined GH emissions (Fig. 1A) and projected surface temperature anomalies (Fig. 1C). LCDI is the perpendicular distance from the diagonal of the emission-temperature relationship, capturing the ratio of the vertical and horizontal change between the two datasets and reflecting the local disparity from the global emission–forcing relationship. Hollow circles represent individual 1° × 1° cells (n = 64,800). (B) Histogram of the global disparity shows that 99% of pixels fall above zero or occur above the diagonal line in (A). (C) Global projection of LCDI across both terrestrial and marine regions. Negative values (cyan) indicate relatively more emissions than temperature shifts, whereas positive values (black and red) signal the inverse. Both panels are derived from projected near-surface warming over 2050–2099 under the IPCC RCP 8.5 scenario.

Regional LCDI inventories and rankings

For interpretive value, we summarized the distribution of LCDI values within larger political, geographic, and ecological boundaries. As any such regional assessment is sensitive to the geometry of the underlying spatial units, we expressed the ensemble’s 10th, 50th, and 90th quantiles, also to convey the frequently substantial LCDI variability within boundaries (fig. S12). We ranked units by the 10th quantile to focus on the contributions from negative LCDI values in each unit. This ranking emphasizes areas of extreme emissions and their disproportionate influence on climate change, with large and heterogenous spatial units such as the United States and China in mind. This ranking, however, does not affect smaller or more homogenous spatial units, such as Belgium or the east Indo-Pacific Ocean, respectively.

The regional LCDI summaries (Fig. 3) capture interactions of population density and economic production as well as human modification of the natural landscape. Regions summarized by a positive LCDI are the dominant pattern, with a global LCDI median of +1.11 (Fig. 2B). Most frequently, positive LCDI regions are northern latitude regions represented by the Arctic Ocean, eastern Europe, Central Asia. In these regions, model simulations indicate that the warming effects of anthropogenic GH emissions are amplified. Although sparsely populated, these high-latitude regions are critical as they support indigenous communities and are ecologically unique, and their ocean and cryosphere play a pivotal role in global climate regulation (11). The regions summarized by negative LCDI are largely located within the densely populated temperate regions such as western Europe, eastern North America, and East Asia. These regions have historically high emissions and relatively small future temperature shifts. Perhaps unexpectedly, several nation states with the most positive LCDI scores are large, sparsely populated countries, where extreme temperature shifts are projected during the 21st century (Russia, Canada, and Finland). Nation states with the lowest LCDI values are smaller, industrialized countries in Europe and the Middle East (Belgium, Netherlands, Germany, and Kuwait). As Fig. 3A presents only the results from 50 nations at the outer extremes, fig. S13 presents expanded results for all 192 United Nations (UN) member countries.

LCDI model outputs aggregated for cells according to (A) UN member state (including their EEZs), (B) ecological biome, (C) anthropogenic biome, (D) geopolitical region, and (E) U.S. state boundaries. Horizontal bars span the 10th to 90th quantiles, and vertical white bars are the median. Bars pool the LCDI outputs from all emission scenarios (RCP 4.5 and 8.5) and 21st century periods (2006–2055 and 2050–2099). Regional units retain the color symbology from Fig. 2 and are ranked by their 10th quantile (see fig. S11). Sparsely populated, northern latitude areas (Russia, Arctic Ocean, and Alaska) have low emissions and extreme warming, whereas densely populated temperate regions (Belgium, western Europe, and New Jersey) have high emissions and relatively small temperature shifts. For display purposes, (A) to (C) show only the outer tails of a larger data series set. The Supplementary Materials present boundary maps for each regional set (figs. S8 to S11) and full versions of abridged series (figs. S13 to S17). The gray vertical line spanning each panel is the median value of each set.

Among the biogeographic groupings, northern high-latitude biomes are generally characterized with positive LCDI scores (Fig. 3B and fig. S14). Temperate deciduous forests and mangroves, however, have the most negative LCDI among ecological biomes. This result is likely due to the high rates of land conversion in mangroves and temperate forests and their subsequent economic development (20, 21) combined with relatively modest projected temperature shifts. Densely populated urban environments and intensive agricultural regions (irrigated crops and rice) exhibit the most negative LCDIs among the anthropogenic biomes (Fig. 3C and fig. S15).

Steep LCDI gradients are found within continents of Europe and Asia (Fig. 3D and fig. S15). Considered in geographical order, western Europe has the most positive LCDI and eastern Europe the second lowest, where East and South Asia have the second and third highest LCDI score, respectively, and Central Asia has the lowest. Consistent with previous results at larger geographic scales, smaller and densely populated U.S. states (New Jersey, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania) exhibit negative LCDI values, while sparsely populated northern states such as Alaska and South Dakota have positive LCDI values (Fig. 3E and fig. S16). Together, the LCDI largely reflects the interplay of projected temperature shifts, with historical human population density and economic production.

DISCUSSION

Global and regional considerations

The spatial resolution of our global emission index was reduced to accommodate the coarser 1° × 1° resolution CMIP5 climate outputs (19). The resolution of our LCDI therefore presents limited information over small spatial units with few pixels (e.g., Kuwait and Connecticut). Comparisons between regional units of varying extents should also be viewed considering the underlying sample size of each unit. Furthermore, as GH emissions are concentrated on but not limited to land (Fig. 1A), LCDI comparisons between UN member states with and without extensive exclusive economic zones (EEZs) should be exercised with appropriate interpretation and inference. Future LCDI analyses that incorporate regionally downscaled global climate outputs can account for mesoscale climatic variability and may better inform regional LCDI comparisons. Using the CMIP5 output, the aim of our LCDI is to generate this information locally while providing true global coverage.

Our global emission dataset combines several individual emission inventories, each of which is subject to sampling errors or a lack of reporting (22, 23). While these emission inventories are influenced by the political or socioeconomic stability of the region, the magnitude of impact of any errors on the ensuing emission products will correspond to the underlying magnitude of economic development of the region. Beyond governance, transparency, and data availability, BC emissions have additional uncertainties because of rapidly shifting technology, consumption rates, and fuel types (24). As BC is an aerosol (an aerial suspension of solid particulate matter), emissions are more easily measured with remote sensing. In addition, our global emission inventory is a first-order description based on local consumption and does not account for emissions embodied in economic trade (25). Future analyses may be improved upon by expanding upon the GH emission inventory we compiled here (table S1), accounting for the geographically distant emissions required to support localized consumption, or couching the results in terms of human population density (see figs. S18 to S20) (26). Here, it was a primary goal to represent the entire planet’s surface, especially the ocean, and this has repeatedly guided our approach (27).

To take advantage of the most informed CMIP5 ensemble output (see table S2), our LCDI focused on the single climate variable of surface temperature anomalies. Although the CMIP5 projections show a larger uncertainty at high latitudes (especially with high-emission scenarios and longer time scale predictions; see fig. S25), there is broad agreement that these regions will experience extreme warming (6) and the CMIP5 temperature signal is considered robust. The ensemble temperature projections, while intuitive and useful for communication, display a general pattern that surface temperatures over land are warming faster than those over the ocean (Fig. 1C). Beyond warming projections, our analysis indicates that three of the five ecological regions with the highest LCDI are in the ocean ( Fig. 3B). Because of the extent, volume, and heat capacity of seawater, our approach using surface temperatures only does not reflect that most of heat generated from anthropogenic climate change is absorbed by the ocean and subsequently manifests in heat waves, hypoxia, sea level rise, extreme rainfall, and mass coral bleaching events. Future approaches to indices of climate disparity, therefore, may also include additional climate change variables (sea level rise, precipitation, etc.) and moreover track domain-specific variables (27) such as sea surface temperature and ocean heat content as they are increasingly reflected in general circulation model (GCM) outputs (28, 29). In addition, how local indices of climate disparity intersect with income (30) may inform efforts to reduce poverty, forced displacement, transboundary migration, and economic inequalities that are driven by climate change (31, 32).

_______________________________________________________________________

Read Also : Will the New Farm Laws Lead to More Greenhouse Gas Emissions From India’s Farms?

________________________________________________________________________

Science-based communication tools

It is generally understood that environmental disturbances exert social influences over a variety of spatial and temporal scales (33). This is an important feature of the climate change dialogue, as the uncertainty, nonlinearity, and scale of climate science all influence how individuals perceive and respond to the climate crisis (9). This complexity has unexpectedly therefore been a common topic—with some arguing that it has received too much attention (34)—in climate change outreach and communication. Studies demonstrate, however, that uncertainties in the magnitude, distribution, and timing of climate change inhibit individual changes in human behavior. These uncertainties may create a false sense of isolation from climate threats (35) and a skepticism or pessimism that individual human agency can improve chronic, global problems (36). Past studies have addressed this issue by focusing on terrestrial climate change impacts only and using coarser country-level emission summaries (37, 38). However, there are substantial socioeconomic differences and inequities (e.g., incomes, technologies, and access) within countries, especially those that are large and contain significant geographic diversity (Fig. 3A). While this may constrain available data, emission impact analyses that use the most resolved and extensive datasets will provide a more comprehensive evaluation of anthropogenic emissions from various spatial units, even if they differ in their basic underlying characteristics and methodologies.

To these points, recent dialogue on climate change collective action has specifically called for communication tools that bring together a more diverse global community and increase the understanding of broad-scale risks (39). The LCDI metric we provide here quantifies the magnitude of local disconnect between GH emissions and temperature shifts, offering a science-based communication tool for transboundary understanding and collective action. This tool may be effective at different geographic scales. At a national level, surveys of adults in the United States (4) indicate that consensus belief in global warming is lower in states where our LCDI is high, and vice versa (Fig. 3D), presenting fresh opportunities for advancing public opinion in those areas and beyond. At the regional scale, our LCDI may help illustrate the need for consumption-based emission inventories that account for GH emissions embodied in economic production and thereby include the trade-related emissions that local consumption requires and enables (25). At the international scale, agreements to reduce global emissions have largely been constrained by retrenched commitments from the United States and China (40), the two nations that arguably possess the greatest internal LCDI gradients.

Our LCDI methods are scalable to accommodate additional pollutants and measures of impact as these data become available. Studies have shown that some anthropogenic emissions (e.g., SO2) are radiatively active yet have minimal or even cooling effects on surface temperature (41–43). Many climate change metrics are available beyond projections of surface warming, but some of these may make more physical or policy sense than others and therefore confer specific interpretive value. Our analysis is based on the ensemble mean differences in surface temperatures, a standard IPCC metric that can be easily translated to general audiences and applied to the temperature target-based climate negotiation framework (44). However, the LCDI can be calculated with probabilistic climate change metrics (such as signal-to-noise ratio; see fig. S26) to incorporate the significance of future temperature shifts considering their historical temperature variation, locally (45). Our combined GH emission layer and LCDI can help to ensure that these dialogues are both policy-oriented and science-based and aligned with the “common but differentiated responsibility” principle established at the foundational 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2).

Communicating climate change impacts on coupled human-natural systems requires a clear understanding of the complex emission–climate change relationship. To our knowledge, our LCDI presents the first global, regional, and national inventory of spatially resolved human-climate disparity over both terrestrial and marine domains. Efforts to apply empirical approaches to disentangle and explicitly quantify the spatial pattern of geographical disparity of human systems to projected climate change should remain an active research field that is engaged with public communication, policy, and decision makers. Our LCDI is dependent on publicly available information and open-source code and can be easily revised to consider additional data inventories and reproduced for applications at different spatial scales. This may serve as a baseline model to highlight the geographically distant climate impacts from local emissions as well as highlight social, political, and economic inequalities across the planet. We hope that these simple illustrations of the complex relationship between the causes and consequences of climate change may advance solutions that have, to date, eluded global efforts to facilitate collective action.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Anthropogenic emission datasets

To build a global layer summarizing anthropogenic GH emissions, we used three well-mixed GH gases (CO2, CH4, and N2O) and BC, an aerosol measured as particulate matter smaller than 2.5 μm (PM 2.5) (24, 46, 47). CO2 represents 80 to 90% of the total anthropogenic forcing in all RCP scenarios through the 21st century (48). Although the direct radiative forcing of BC has been debated (19, 20) (average, ~1.1 W m−2; range, 0.17 to 2.1 W m−2), it is considered the second leading GH agent. Together, these four agents comprise most of the global radiative forcing (table S1). We retrieved global CO2, CH4, and N2O emission data from the Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR v5.0). EDGAR estimates CO2 emissions from 1970 to 2018 and CH4 and N2O emissions from 1970 to 2015, annually, at a 0.1° × 0.1° resolution through comprehensive sector-based accounting of fuel use by fuel type as well as cement production (16). The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications (MERRA-2) reanalysis product provided the global BC emission data, accessed from the Giovanni GES-DISC portal from NASA. MERRA-2 uses the modern satellite measurements provided by the Goddard Earth Observing System Data Assimilation System Version 5 (GEOS-5) and synthesizes the various observations collected monthly from 1980 to present at 0.5° × 0.625° resolution (17). Like EDGAR, the MERRA-2 reanalysis dataset also includes shipping and aircraft-based emissions and is more accurate and stable compared to the remote sensing estimates alone (49, 50).

Generation of a global emission index

To account for the different measurement time periods of these emissions, we averaged the annual emissions of each dataset over its historical chronology (fig. S1). To align all emission agents to a similar scale of impact (i.e., CO2 equivalents) and facilitate a global summary, we multiplied the raw emission values of BC, CH4, and N2O by their global temperature potential (GTP) (6, 51), using the average of the 20- and 100-year values (table S3 and fig. S2). Here, CO2 is the GTP reference point, with a value of 1 (6). Next, we reprojected the MERRA2 BC data to the EDGAR dataset resolution using bilinear interpolation (52) and summed all layers (fig. S2). This provides a spatially resolved, global summary of the top four GH agents over the last half century (49 years).

_______________________________________________________________________

Read Also : First-ever study of all Amazon greenhouse gases suggest the forest is worsening climate change

________________________________________________________________________

Future temperature anomalies

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Climate Change Portal (www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/ipcc/) provides surface temperature anomalies from the GCM outputs from CMIP5 (19). The portal provides RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 CMIP5 experiments separated by the magnitude of radiative forcing (W m−2) in 2100. We retrieved future surface temperature anomalies from all available CMIP5 models under the RCP 4.5 (32 underlying models) and 8.5 (37 underlying models) scenarios for the 2005–2055 and 2050–2099 periods (full details in table S2). For each of the four RCP and time period combinations, we generated an ensemble mean of surface temperature anomalies for the available CMIP5 models, based on the default 1956–2005 reference period, at a 1° × 1° resolution (fig. S3). Besides being the most informed GCM output globally, surface temperature changes are likely the single most important variable of climate change influencing both natural and human systems (2, 6, 53).

Disparity index of emissions and future temperature anomalies

We developed a global, spatially explicit index of the relationship between local anthropogenic emissions and projected local surface temperature anomalies. For all cells (n = 64,800 at 1° × 1° resolution), we quantified the perpendicular distance from the diagonal spanning the extent of the two datasets (also see Fig. 2A) (54). This LCDI is accounted for by the formula

(1)where ti is the local temperature anomaly, ei are the local aggregated anthropogenic emissions, and β is the ratio of the extent within e and t such that β = (tmax − tmin)/(emax − emin). We calculated LCDI for all four combinations of RCP 4.5, RCP 8.5, and 2006–2055 and 2050–2099 projections (figs. S5 and S6) after winsorizing the emissions and projected temperature layers, each to their 99.99th quantile (55).

Summarizing disparity within regions

We summarized LCDI values within various political and ecological boundaries (figs. S8 to S11). The Marine Regions database (56) provides EEZ boundaries, and the R rnaturalearth package (57) provides boundaries for UN member states and the United States. We grouped terrestrial and marine ecological regions (58, 59) into broader nested categories (realms and biomes, respectively; table S4) and aggregated UN member states into larger geopolitical regions (subregions). This provides boundaries for 192 UN member states (see table S5 for excluded entities), 22 geopolitical regions, 31 ecological regions, 21 anthropogenic biomes (60), and 50 US states. For UN member states, we expanded their national borders to include their EEZ and oversea territories (61). For transboundary cells, we assigned the cell to the region accounting for most of its area. We then summarized the LCDI values considering the four output combinations of RCP 4.5, RCP 8.5, and 2005–2055 and 2050–2099 projections (fig. S5). Next, we generated histograms of the pooled LCDI outputs within each region and, because of the skew of the data (fig. S12), ranked each region by the 10th quantile of the LCDI values.

All the data and source code used in this study are available in open-access third-party repositories: GitHub (https://bit.ly/395gNMZ) and Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/b53fy/).