For years, scientists hadn’t been able to confirm how the northern lights cast their spectral glow across the sky.

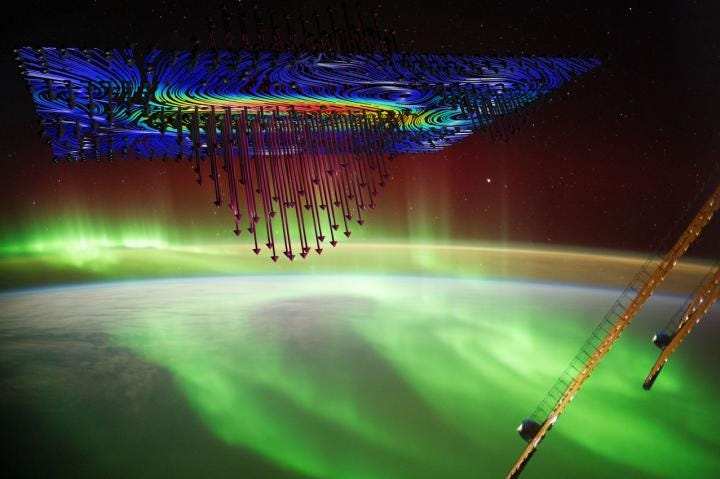

But they’d long held a theory. First, eruptions on the sun release a stream of charged particles called solar wind. Those particles interact with Earth’s magnetosphere – the region around the planet controlled by its magnetic field. In the process, the field launches powerful electromagnetic waves in the direction of Earth’s surface.

Electrons then hitch a ride on these waves and surf their way toward Earth’s upper atmosphere. Once there, they collide with atoms and molecules in the brilliant light show known as the aurora.

But scientists struggled to prove this theory for decades. The distances of space involved are far too vast to recreate inside a lab, and spacecraft technology only enables researchers to measure electrons and electromagnetic waves separately at different altitudes.

Recently, however, scientists managed to simulate the conditions that produce an aurora inside a vacuum chamber. In a new study, they reported that the predominant theory is indeed correct. Electromagnetic waves called Alfvén waves transfer energy to electrons, giving the particles an accelerated push toward Earth. Electrons can then surf the waves, ultimately reaching speeds of up to 45 million miles per hour.

“The idea that these waves can energize the electrons that create the aurora goes back more than four decades, but this is the first time we’ve been able to confirm definitively that it works,” Craig Kletzing, a physics professor at the University of Iowa who co-authored the study, said in a statement.

A giant vacuum chamber to simulate ‘electron surfing’

Russian physicist Lev Landau first proposed the idea that electrons gain speed by surfing electromagnetic waves – a process now known as Landau damping – in 1946. Kletzing set out to test that theory roughly two decades ago, but before that could happen, scientists had to recreate the conditions of Earth’s magnetosphere.

Their solution was the Large Plasma Device at the University of California, Los Angeles – a nearly 66-foot-long vacuum chamber that produces enough plasma (the ionized gas that makes up much of our universe) to support Alfvén waves. “They thought it should take a few years,” Gregory Howes, an associate professor at the University of Iowa, told Insider. “Well, it turned out it was a lot harder problem to do in the laboratory than was initially anticipated.”

“This had never been proven directly in the laboratory that this actually worked,” Howes said. “So being able to show in a real plasma that this theoretical idea actually comes to pass was really the major challenge.”

Eventually, the simulation showed – and mathematical models confirmed – that this process of electron surfing results in brilliant light shows on Earth.

“It solves the key piece of the puzzle that was missing to understand what are called discrete auroral arcs,” Howes said. “Those are the shimmering curtains of light that you think of when you think of aurora.”

Read Also : Case study: Mandi system of Punjab v/s Bihar, amidst the ongoing protest

Auroras don’t form until the electrons are close to Earth

The researchers stopped short of actually recreating the glowing spectacle of the northern lights, though. That’s because the phenomenon occurs at a much lower altitude than Alfvén waves, and under a different set of conditions.

Earth’s magnetic field launch Alfvén waves about 80,000 miles above the planet’s surface, Howes said. Electrons in the magnetosphere then start surfing the waves at an altitude of around 10,000 miles.

Researchers settled for a much dimmer light show inside the lab.

“The plasma itself does glow – it’s very pretty,” Howes said. “But the glow that you think of as these accelerated electrons hitting the plasma is not what we see.”

I conceive this web site has some really good info for everyone :D. “Time–our youth–it never really goes, does it It is all held in our minds.” by Helen Hoover Santmyer.