Finding protein-rich foods that are good for the climate can be complex. Isabelle Gerretsen digs into the data to understand which food choices can help us curb emissions.

When it comes to reducing our individual carbon emissions, one of the most impactful steps we can take is to eat more sustainably. Global food production is responsible for 35% of all human-caused greenhouse gas emissions. While animal products account for the bulk of our dietary emissions, they provide only 20% of the world’s calories.

Animal products, such as dairy, eggs, fish and meat, are known to be good sources of protein, and getting the right amount of protein is essential for our bodies to grow and repair (Read more about how much protein we really need to consume).

For those who want to eat a low-carbon diet that is also nutritious, getting the right level of protein can be challenging. The picture is complicated by the huge range of products available to us, many of which assert that they are “carbon neutral” or “sustainable” without always backing up these claims.

So, what would a protein-rich, low-carbon diet really look like? Just how bad for the climate are meat and dairy? How much more sustainable is it to only eat plant-based proteins, such as tofu, chickpeas and peas? Is it better to cut out cheese or chicken? Which animal-free alternatives have the lowest emissions’ output?

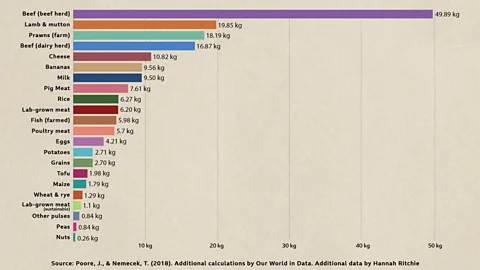

BBC Future set out to answer these questions, using data from the largest ever analysis of food systems, compiled by Joseph Poore, a researcher at the University of Oxford, and Thomas Nemecek, who studies the lifecycle of food at Swiss research institute Agroscope.

________________________________________________________________________

Read Also : Case study: Mandi system of Punjab v/s Bihar, amidst the ongoing protest

________________________________________________________________________

Meat

According to the analysis, beef generates 49.9kg of CO2 equivalent, or CO2e, per 100g of protein, equivalent to the amount in 2.35 steaks. The proteins with the second-highest greenhouse gas (GHG) footprint are lamb and mutton, which generate 19.9kg of CO2e per 100g.

What is CO2e?

CO2 equivalent, or CO2e, is the metric used to quantify the emissions from various greenhouse gases on the basis of their capacity to warm the atmosphere – their global warming potential.

“There’s so much emphasis on beef that people often forget about other types of meat and their impacts,” says Anne Bordier, director of sustainable diets at the World Resources Institute.

Cows, sheep and goats are all ruminants, animals with more than one stomach chamber that belch out methane when they digest their food. Although shorter-lived in the atmosphere, methane is a highly potent gas that has a global warming impact 84 times higher than carbon dioxide (CO2) over a 20-year period.

In addition to livestock’s high methane output, greenhouse gases are emitted to produce and transport animal feed and run the livestock farms, says Sophie Marbach, a physicist and researcher at the National Centre for Scientific Research in France who carried out an analysis of the carbon footprint of meat and dairy proteins in 2021.

Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018

Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018Beef from a dairy herd has a lower greenhouse gas footprint than meat from a beef herd because you get more food in return for all the resources you invest in the cow (feed, land, water and fertiliser), says Bordier. “[In addition to beef], these cows produce milk, which also tends to be used as feed [for other animals]… So it’s more efficient overall,” she says.

Dairy cows usually produce high milk yields for about three years, after which they are slaughtered and their meat is used for beef.

Meat from small, non-ruminant animals, such as chicken, turkey, rabbit and duck, has a much lower GHG footprint than beef and lamb. Chicken, for example, has a GHG footprint almost nine times lower than beef’s – generating 5.7kg of CO2e per 100g of protein.

That’s “quite low”, says Sarah Bridle, professor of food, climate and society at the University of York in the UK. “It is really similar to farmed fish and eggs.”

Pork’s GHG footprint (7.6kg) is about 6.5 times lower than beef’s and 1.4 times higher than poultry’s (5.7kg).

Dairy

It is cheese, not chicken or pork, that generates the third-highest emissions in agriculture, after lamb and beef.

“There’s this consensus that ‘being vegetarian is great’, but then we sort of forget that cheese is actually pretty carbon intensive,” says Marbach, noting that this is due to cows’ high methane output and the fact that they require “a lot of inputs for not much output”.

The GHG footprint of cheese (10.8kg of CO2e per 100g of protein) is almost twice as high as chicken’s and also higher than pork and eggs (4.2kg of CO2e).

The dietary emissions can vary greatly depending on the type of cheese you’re eating. Harder cheeses, such as parmesan, are more carbon-intensive than soft cheeses because they are made with more milk, says Bridle. Soft cheeses contain more water – there’s 50% more water in cottage cheese than in cheddar, for example, she says.

________________________________________________________________________

Also Read : Can carbon removal save us?

________________________________________________________________________

The GHG footprint of cow’s cheese is similar to that of goat’s or sheep’s milk cheeses “because they’re all ruminants,” says Bridle. “But cow’s cheese is probably the most efficient because dairy cows produce vast amounts of milk.” According to data from the UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, a dairy cow produced an average of 8,200 litres (1,800 gallons) last year.

Alamy

AlamyYoghurt, meanwhile, is surprisingly low-carbon, 2.7kg of CO2e per 100g of protein, as not much milk is needed to produce it (much less than in the case of cheese) and there are a number of by-products, such as cream and butter, which means the GHG footprint is distributed across numerous food items,says Marbach.

Plants

Animal products are responsible for 57% of global food-related emissions, compared to plant-based foods which contribute 29% of the total.

The UK’s Climate Change Committee (CCC) has recommended a 20% reduction in meat and dairy consumption by 2030, rising to 35% by 2050 for meat, to meet the country’s climate goals.

The lowest emissions option would be to adopt a vegan diet and cut out meat and dairy altogether. If the whole world went vegan, global food-related emissions would fall by up to 70% by 2050, according to a study by the Oxford Martin School at the University of Oxford.

A diet rich in peas, pulses and nuts can be incredibly low-carbon. Producing 100g of protein from peas emits just 0.4kg of CO2e. This is almost 90 times less than getting the same amount of protein from beef. Other pulses, such as lentils, have a GHG footprint of 0.8kg of CO2e. Tofu production, meanwhile, generates 2.0kg of CO2e per 100g – these emissions are mostly linked to the clearance of land for soy production, says Bridle.

By crossbreeding wild chickpeas with cultivated varieties, US company Nucicer has created high-protein chickpea powder, which it says also lowers the CO2e of the crop. The powder can be used as gluten-free flour in pasta and baked goods.

By increasing the protein content, Nucicer is able to produce more protein per acre and reduce the overall amount of energy and water needed, says Kathyrn Cook, the company’s chief executive and cofounder. “That really helps with the environmental impact of our protein sources,” she says. Chickpeas are also highly water-efficient and fix nitrogen from the air into the soil, which is vital for plant growth, she adds.

Wolfgang-Kaehler/Getty-Images

Wolfgang-Kaehler/Getty-ImagesFish and seafood

When it comes to fish and seafood, it is more difficult to calculate the GHG footprint. It can vary greatly depending on the species and how it is caught.

Farmed prawns have a much higher footprint (18.2kg of CO2e per 100g) than farmed fish (6.0kg of CO2e). This is because mangrove forests, which store huge amounts of carbon, are often destroyed and converted into prawn farms.

________________________________________________________________________

Read Also : What Should the SEC Require in Climate Change Disclosures?

________________________________________________________________________

But farmed bivalves, including mussels, oysters, scallops and clams, have a much lower GHG, about six times lower than farmed prawns and roughly 3.5 times lower than farmed fish,says Jessica Gephart, assistant professor in environmental science at the American University in Washington DC.

In 2021, Gephart and her colleagues analysed the environmental impact of seafood across a range of factors, including greenhouse gas emissions, pollution and freshwater use.

Farmed bivalves scored the best across the board. However, bivalves caught in the wild did not perform nearly as well when it came to greenhouse gas emissions – they emit five to 10 times more emissions as their farmed counterparts, says Gephart.

Farmed bivalves don’t require animal feed as they filter nutrients from the water and can be harvested without a large amount of energy. Wild bivalves are often caught by dredging – which involves towing large, rigid nets along the seafloor. It’s a carbon intensive process which disturbs carbon stored in the sediment and results in the release of CO2, which acidifies the ocean.

One study estimates that seabed dredging produces as much as one billion tonnes of CO2 annually – equivalent to global aviation emissions and greater than those of Germany.

Lab-grown protein

From cellular meat, which uses cells harvested from live animals, to plant-based meat made from soy or pea protein, and cow-free dairy produced using precision fermentation, we now have a huge range of meat and dairy alternatives to choose from if we wish to avoid animal products.

But how do they compare to traditional meat and dairy, when it comes to emissions?

According to a 2020 study by Raychel Santo, a researcher at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, plant-based meat generates 1.9kg of CO2e per 100g, while cellular meat produces 5.6kg, compared to beef’s GHG footprint of 25.6kg. While emissions for cellular meat were significantly lower than traditional meat, they were five to 21 times higher than emissions from plant proteins, such as pulses, tofu and peas, Santo’s research found.

A large proportion of cellular meat’s footprint comes from the energy required to manufacture the products, says Santo. The cells harvested from animals are grown in bioreactors, which are highly energy intensive.

“Plant-based meat substitutes have smaller GHG footprints than most farmed meats and cell-based meat, but wild tuna (1.2kg), insects (0.9kg), tofu (1.2kg) and less processed pulses (0.4kg) and peas (0.3kg) have the lowest footprints of all protein-rich foods,” says Santo.